Applications I // Conceptual Particle Filter

Today

- Applications Discussion I: The Intersection of AI and Robotics

- Bayesian Filtering (and the Particle Filter)

- Motion Models: Computing Relative Motion

- Observation Models: Computing Liklihoods

For Next Time

- Work on the Broader Impacts assignment Part 1, due on September 30th at 7PM (tomorrow).

- We will have a class discussion on Thursday Oct. 2nd (next class).

- There is an assignment on the discussion – plan for ~7 minutes for each person in the group to share and ask questions.

- Review the feedback form that you’ll be filling out for every presenter for a sense of how you might present your robot.

- Complete the Particle Filter Conceptual Overview due Friday October 3 by 7PM

- Form a team + update Canvas; and work on the Robot Localization project

- Demos due on Thursday October 16 by Class

- Code + Writeups due on Friday October 17th 7PM

- Consider whether there is feedback you’d like to share about the class

Applications I: The Intersection of AI and Robotics

Throughout the second module, we will be taking a tour of topics the class flagged as mutually interesting areas to learn more about robotics applications and implications.

First up, we’re going to discuss the intersection of AI and Robotics. In your group, please fill out brief notes from your discussion using this form. Please be sure to answer the poll question at the bottom!

Classifying Embodied AI Systems

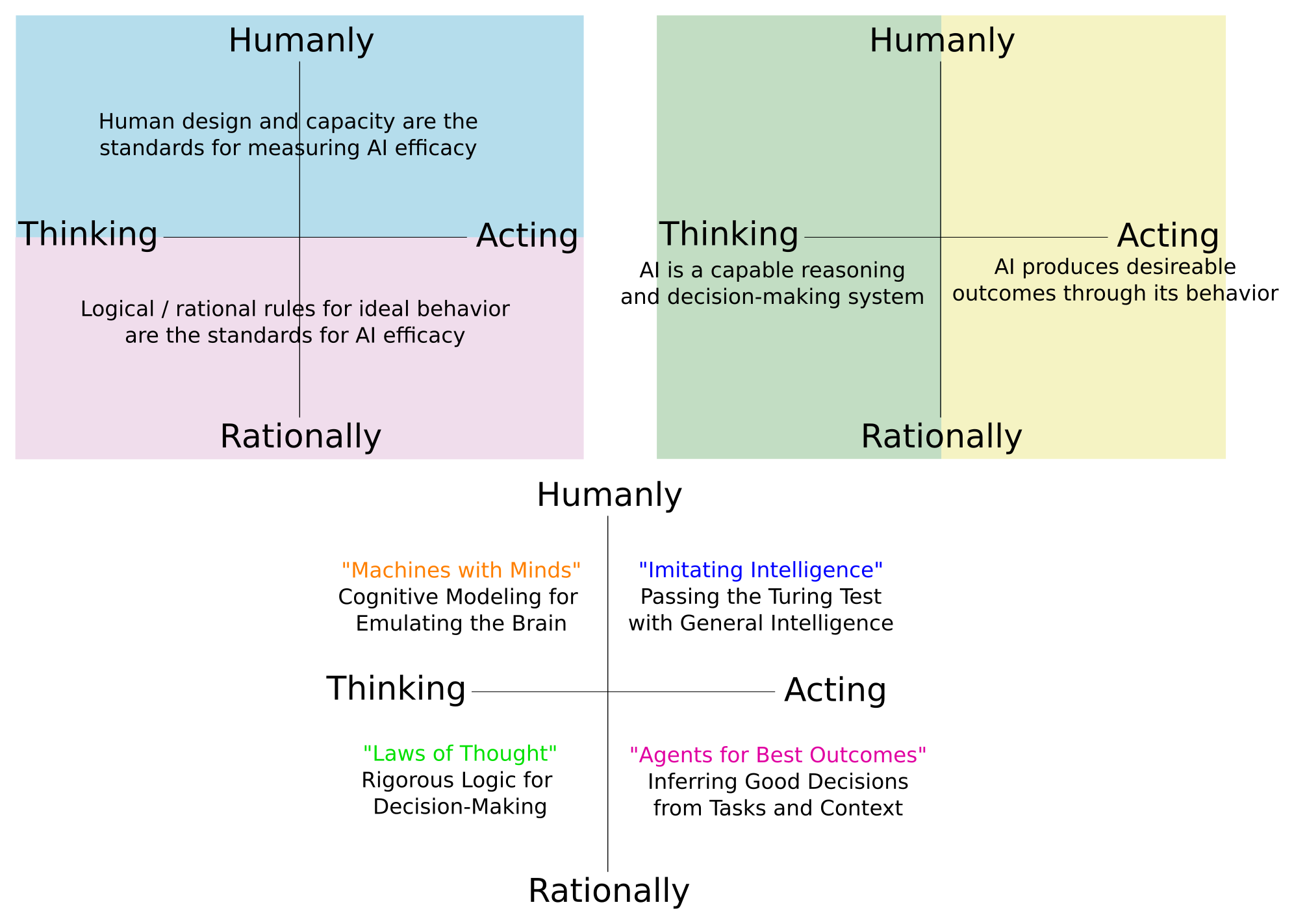

In a seminal textbook on Artificial Intelligence, Stuart Russel and Peter Norvig divide the field across two axes: Thinking vs Acting; and Human-Like vs Rational.

Where do different robots or robotics disciplines fall along these lines?

By virtue of being embodied; robots tend to fall along the “Acting” categories – perhaps operationalizing computer science discoveries in the “Thinking” categories to get the job done.

Let’s consider then the difference between Acting Humanly and Acting Rationally. How would you sort the following robots between these categories?

- At-home care and companion robots

- An autonomous planetary explorer

- A self-driving taxi

- Manufacturing-line arms

- Warehouse pack-and-stack robots

- Deaf-blind signing interface (e.g., Tatum Robotics)

- Automated solar installers

- Your selected Broader Impacts Robot

After you’ve taken a pass at sorting these robots, pick one of the following two reflection questions and discuss with your table group:

- What heuristics were you using to sort the robots? Did task, context, or something else matter the most in your sorting? Why or why not?

- For your “Acting Humanly” robots, what are the key technical challenges that would need to be overcome in implementing these robots? And for the other category? What is shared and what is unique?

Implementing Embodied AI: Dealing with Novelty

Those of us familiar with the generative AI explosion of the last 2 or so years know that apps like Chat-GPT, Claude, CoPilot, NotebookLM, and many more systems are trained on massive datasets of text, imagery, video, and audio in order to produce impressive pattern-predicted output for given prompts. For the casual conversation with an AI chatbot, the output can be uncannily human-like.

But when have you seen these systems fail? What were you attempting to do or discuss with the genAI system when you started getting unusable, nonsensical, irrelevant, or simply strange output?

Novelty in AI and robotics is the encountering of a scenario (rendered through measurement from a sensor or set of sensors) that is outside of the distribution of previously seen scenarios. Remember, many large-data AI systems are essentially very good interpolators, not extrapolators.

While for large language models (LLMs), extremely niche topics may be the thing that finally trips up the chatbot, for embodied robotic systems, novelty is a much more common implementation hazard. Some reasons for that:

- Robots run in real-time with streaming measurements that for some arbitrary time horizon can be a unique sequence

- Robots may encounter many one-off scenarios that can get drowned out in standard training regimes as “noise”

- Robots are in the “real-world” with multi-agent (other robots, other people) complexities

- Every instantiation of a robot will have its own noise characteristic

- Some robotic tasks are literally predicated on the notion of novelty (e.g., planetary exploration robots)

- What are some other reasons/scenarios?

The 1-5% of self-driving that has yet to be “solved” can largely be chalked up entirely to the challenge of handling novelty with the classical and modern ML and AI methods used under the hood.

Pick one of the robots from the last part of the exercise, choose a “task” that would be appropriate for this robot to do, and discuss with your group the following:

- What aspects of this task could lend themselves to generative AI or other large-data AI models?

- What aspects of this task would require dealing with novelty in typical use?

- What are some of the ways you might suggest handling novelty when this system encounters it? (you could think about whether there are rules that could be encoded, prior knowledge that can be embedded in the system, safety features that would be installed, a different AI or ML toolkit that could be used outside of large-data training systems, etc.)

Bayesian Filtering and the Particle Filter

For your projects, you’re implementing a particle filter, which is a subclass of algorithm under the more general category of Bayesian filters. A Bayesian filter is a recursive, or sequential, algorithm – for localization, this means that the robot’s state estimate is refined iteratively as observations or actions are taken.

At a high-level, the steps of a Bayesian Filter are:

- Initialize with an estimate of the first pose

- Take an action, and predict the new pose based on the motion model

- Correct the pose estimate, given an observation

- Repeat steps 2 and 3, ad nauseum (or until your robot mission is over)

We can compare that to the outline of a particle filter we reviewed last class:

- Initialize Given a pose (represented as \(x, y, \theta\)), compute a set of particles.

- Motion Update (AKA Prediction) Given two subsequent odometry poses of your robot, update your particles.

- Observation Update Given a laser scan, determine the confidence value (weight) assigned to each particle.

- Guess (AKA Correction) Given a weighted set of particles, determine the robot’s pose.

- Iterate Given a weighted set of particles, sample a new set.

Prediction

During the prediction step, the current estimated pose of the robot is updated based on a motion model. The motion model captures how a control input may be mapped to the real world (what noise may be applied, for instance). Prediction will always increase the uncertainty we have about where the robot is in the world (unless we have perfect motion knowledge). Prediction asks: given where I think I am, where will I end up after I take this action?

Correction

To reduce (or attempt to reduce) our uncertainty, we can look around us with an observation model (which will also capture noise in our measurements). Correction asks: given what I am measuring, what is my likely pose based on my estimate of where I may be?

The Particle Filter

A Bayesian filter, in its purest form, asks us to work with continuous probability distributions, and that is computationally challenging (nigh intractable) most of the time for practical robotics problems. The particle filter addresses these computational challenges by allowing us to draw samples from our probability distributions and apply our prediction and correction steps to each of those samples in order to get an empirical estimate of a new probability distribution. In this way, the particle filter is a Monte Carlo algorithm, and leverages the law of large numbers to “converge” towards the optimal answer. (You can get a sense about why sampling works to find complex distributions by playing with this applet).

Particle Filter Conceptual Overview

For the rest of class, you’ll work in your project teams towards assembling your conceptual overview of your to-be-implemented particle filter. Be sure to read over all of the assignment page for this project before starting! There is some sample code you will want to run to get a sense of what the full project scope is!

Prediction: The Motion Model: Computing Relative Motion

One part of your particle filter will involve estimating the relative motion of your robot between two points in time as given by the robot’s odometry.

Suppose you are given the robot’s pose at time \(t_1\), and then again a measure at \(t_2\). What are some ways that you might compute the robot’s change in pose between these times? What coordinate system(s) do you want to work in? Work with the folks around you to discuss your ideas; utilize your conceptual overview as a tool for the discussion!

Note: Our coordinate transforms activity from a few classes ago might be inspirational for finding an approach here.

Note: while probably not needed for dealing with 2D rotation and translation, the

PyKDLlibrary can be useful for converting between various representations of orientation and transformations (e.g., see this section of the starter code). This is also a helpful reminder – there is skeleton and helper code you may want to be getting familiar with for your project…

One Approach: Homogenous Transformation Matrices

One way to think about the relationship between poses \(t_1\) and \(t_2\) is through simple translation and rotation. Here is a walkthrough of that technique as well as a video version from Paul:

Note: a mistake is made in this video when writing the origin offset (at 8:37 into the video). This doesn’t change the substance, but watcher beware!

Correction: The Observation Model: Likelihood Functions

One of the key steps of your particle filter is to compute the weight of each particle based on how likely the sensor reading from the particle is, given the map. There are tons of possible ways to compute this weight, but we recommend using a likelihood field function. Computing a likelihood field relies on the following steps:

- Cast the sensor measurement into the world coordinate frame relative to each particle’s frame of reference.

- Determine the closest obstacle in the map based on your sensor measurement location.

- Compute the distance between your sensor reading and the closest obstacle.

- Assign the likelihood of your sensor reading as the probability of your distance measurement + small stochastic noise.

The secret sauce here is in your closest obstacle identification, distance measurement probability, and your stochastic noise…let’s consider the following:

update_particles_with_laser

The first step is to determine how the endpoints of the laser scan would fall within the map if the robot were at the point specified by a particular particle. You can do this by drawing some pictures and pulling out your trigonometry skills!

Next, you will take this point and compare it to the map using the provided get_closest_obstacle function (hint: you may want to be getting familiar with this code). Once you have this value, you will need to compute some sort of number that indicates the confidence associated with it. Finally, you will have to combine multiple confidence values into a single particle weight.

Distance Confidence and Gaussian Distributions

A Gaussian (or normal) distribution is an incredibly useful probabilistic representation used widely in robotics; the reasons are:

- It has a closed-form solution for sampling

- It has a closed-form solution for assigning probability to a sample

We’re interested in using a Gaussian to allow us to represent our confidence in the distance measurement we compute in the previous step. We’ll draw out a picture to see how this manifests in our Neato world.

Setting the variance term in our Gaussian distribution sets the effective confidence bounds we have on distance. This is a parameter you can set experimentally or through an optimization based methodology (if you had a lot of data to work with!)

Stochastic Noise

We know that our sensor readings are likely not perfect, and realistically, neither is the map. To account for some amount of error in those systems, we can add noise drawn from a Uniform distribution to our probability estimate.

Consult Probabilistic Robotics for more Detail

Consider consulting Probabilistic Robotics for more details on using range-finders and likelihood functions (Specifically chapter 6.4).

Limitations

This method ignores the information embedded in ranges that “max out” the sensor reading (the vehicle is in empty space). This method also requires tuning a few parameters for your noise and confidence probability functions.

Combining Multiple Measurements

We typically have more than one range measurement at any time (that’s the power of a lidar!), so we need to consider ways to combine the likelihood of each of our scans to get to one particle weight. Some options may be:

- Average the PDF values across the measurements

- Multiply the PDF values across the measurements

- Something in between?

It turns out these different approaches are all used in various forms in within the particle filters in ROS. For example, there is a really weird way of combining multiple measurements in the ROS1 AMCL package. See this pull request for some interesting discussion of this method.

In ROS2, it seems they still have the old method but there is another method that seems more principled (but may perform worse?).

Possible Extensions (For Your Consideration)

Here are some possible extensions on the particle filter if you’d like to pursue them. In the open work time we can provide more detail on how these might work.

- I want to solve the robot kidnapping problem (unknown starting location)

- I want to re-implement the parts of the filter that were written for me (interactions with ROS)

- I want to experiment with laser scan likelihood functions

- I want to try to implement ray tracing instead of the likelihood field

- I want to understand in greater detail the connection between Bayes’ filter and the particle filter

- I want to make my particle filter more computationally efficient

- I want to experiment with landmark-based likelihood functions

- I want to move my robot based on my pose uncertainty